In the previous post, I described how the Tax and Penalty Minimization (TPM) method can greatly reduce your Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) and thus your total lifetime tax bill – resulting in significantly higher final total assets.

But as I wrote that post, one question kept popping into my head: instead of striving for a $0 tax bill until age 72 (as is the default in the TPM method), could it be worth it to pull more from your pre-tax accounts (beyond the standard deduction) and thus pay a small amount of taxes earlier in your retirement to further reduce your pre-tax account balance and thus reduce RMDs and taxes after age 72 (soon 75)?

Let’s find out.

The Idea

So if the TPM method greatly reduces RMDs compared to the traditional withdrawal method by reducing the pre-tax account over time (taking full advantage of the standard deduction every year), pushing beyond the standard deduction each year (or some of the years) would theoretically reduce your pre-tax account even further and thus your RMDs would also drop.

This idea might seem like a slam dunk initially – why not pay taxes in a much lower tax bracket before the RMDs start, which will likely push you into a much higher top tax bracket?

But is the tax drag on the growth of your portfolio more powerful than the tax savings you’d see after RMDs start? That’s the trade-off we need to consider.

Some Research

When this question first popped into my head, I wondered if someone had already answered it.

I found some results, but in general it was simple statements about possibly converting some of your pre-tax accounts to a Roth IRA. Nothing about the trade-off of lost growth early in life versus tax savings from lower RMDs.

I also searched google scholar, but nothing jumped out at me as relevant. Perhaps I’m not using the correct search terms somehow.

If you’re aware of someone else that has considered this question, please let me know in the comments! Especially if they came to a different conclusion than I did.

Back-Of-The-Envelope Example

Before diving into full fidelity simulations to try to answer this question, I thought I’d try a greatly simplified scenario to see if it gave a promising result.

Starting with a “toy problem” is a good idea to do in general when you’re tackling a new analysis and testing new tools.

Let’s say you have $2M in your 401K at age 71, and $20K in a cash account. Your IRS filing status is Single.

No Extra Withdrawal

If you keep your standard income at the standard deduction (per the TPM method), you’ll have zero taxes (assuming your LT cap gains are also within the 0% tax bracket) and your assets will grow to $2,000,000*1.07 + $20,000 = $2,140,000 (401K) + $20,000 (cash) = $2,160,000 the next year (assuming a 7% after-inflation ROI for invested assets).

Now that you’re 72, you’ll have to take out $2,140,000 / 27.4 = $78,102.19, which counts as standard income. You then stick that entire amount in a post-tax account.

Using 2022 tax rates, you’ll owe $9,950.48 taxes on that $78,102.19 income.

So after paying taxes, you’ll have a total asset balance of ($2,140,000 – $78,102.19) (401K) + $78,102.19 (taxable/brokerage account) + $20,000 (cash) – $9,950.48 taxes = $2,150,049.52.

$40K Extra Withdrawal

Restarting at age 71, what if you took an extra $40K out of your 401K (placing it into a taxable account), on top of your standard deduction, with the goal to reduce your RMDs but staying in the lowest tax brackets. Given the single status tax brackets, that $40K is taxed at 10% up to $10,275 and 12% after that. So you pay 0.1*$10,275 + 0.12*($40,000 – $10,275) = $4,594.5 in taxes when you’re age 71.

Thus your new balance at age 71 is ($2,000,000 – $40,000) pre-tax + $40,000 (taxable/brokerage account) + $20,000 cash – $4,594.5 taxes = $2,015,405.50.

Now if your 401K and brokerage account grow by 7% over the next year, you’ll have a total of ($1,960,000)*1.07 pre-tax + $40,000*1.07 brokerage + $15,405.50 cash = $2,097,200 pre-tax + $42,800 brokerage + $15,405.50 cash = $2,155,405.5 total.

Since you’re now 72, you’ll have to take out $2,097,200 / 27.4 = $76,540.15 as an RMD, which counts as standard income. You then stick that entire amount in a post-tax account.

Using 2022 tax rates, you’ll owe $9,606.83 taxes on that $76,540.15 income.

So after paying taxes, you’ll have a total asset balance of ($2,097,200 – $76,540.15) (401K) + ($42,800 + $76,540.15) (taxable/brokerage account) + $15,405.50 (cash) – $9,606.83 taxes = $2,145,798.67.

So by taking out an extra $40K from your 401K when you’re 71 (staying in the lowest tax brackets), at age 72 you will have $2,145,798.67 instead of $2,150,049.52. You will be $4250.85 poorer!

Hmmm…. that’s not a good sign for this idea of taking more out of your pre-tax retirement accounts than the standard deduction prior to RMDs starting.

Example Scenario

Perhaps we got unlucky with that back-of-the-envelope calculation. Let’s take a look at a more realistic scenario.

Chloe and Chris are 40 and 38 year old early retirees, filing as married filing jointly, with the following attributes:

- $400K in standard pre-tax accounts ($200K each)

- $100K in 457b pre-tax accounts ($50K each)

- $400K in a post-tax account (i.e., “taxable” or “brokerage” account)

- $100K in Roth IRA accounts ($50K each), with $60K in original contributions ($30K each)

- Total of $1M in assets

- $10K in annual qualified dividends from their post-tax account

- $100 in annual non-qualified dividends from their post-tax account

- $34K / year per year in social security income ($17K each) once they turn 67

- Before Chris turns 65 and thus they can both get medicare, they need to target an income of $50K for ACA subsidies

- $40K in expenses each year

- Their expenses will go down by $800 per month when Chloe turns 66, due to paying off their mortgage

We also assume a 7% after-inflation ROI each year for all invested assets.

Note that compared to the previous post using this same scenario, I moved the $20K cash into the Roth account (increasing the total balance and total contributions by $20K) to avoid issues I ran into during the analysis. Long story short, the larger extra withdrawals I tried created tax bills that necessitated dipping into the cash reserves, which threw off comparisons to scenarios that didn’t touch the cash, since there is no ROI for the cash account.

We’ll run a 52 year simulation with the TPM withdrawal method, until Chloe is age 92 and Chris is age 90.

One Year Before

Let’s say we want to increase the pre-tax withdrawals beyond the standard deduction just one year before RMDs start, which is 73 for Chloe and 71 for Chris (because the TPM method depleted Chloe’s pre-tax assets first, to put off RMDs as long as possible).

So let’s try a bunch of different withdrawal amounts, from $0 to $9K in $500 increments.

And let’s also run the simulation without any additional withdrawal amounts, acting as our baseline.

For each of these amounts, we’ll plot a couple different things:

- The final difference in total assets compared to the baseline – “Final Total Diff”

- The largest amount that the total asset balance falls below the baseline (i.e., the worst case scenario if you were to take larger withdrawals to reduce RMDs and then died before seeing any benefits of lower RMDs) – “Minimum Total Diff” (because the minimum is the largest magnitude amount below the baseline)

You can see that this difference is a simple linear downward slope from $0 – so not only is there no benefit from increasing Chloe and Chris’ standard income the year before RMDs start, the total final deficit becomes larger as we increase the withdrawal amount from Chloe’s 401K.

This result seems to agree strongly with the back-of-the-envelope example above that it does not make sense to withdraw more than the standard deduction before RMDs start to reduce your RMDs.

Also note that the Final Total Diff line is higher than the Min Total Diff, which is logical because reducing the RMDs does reduce Chloe and Chris’ taxes a bit – just nowhere near enough to make it worth paying taxes before RMDs.

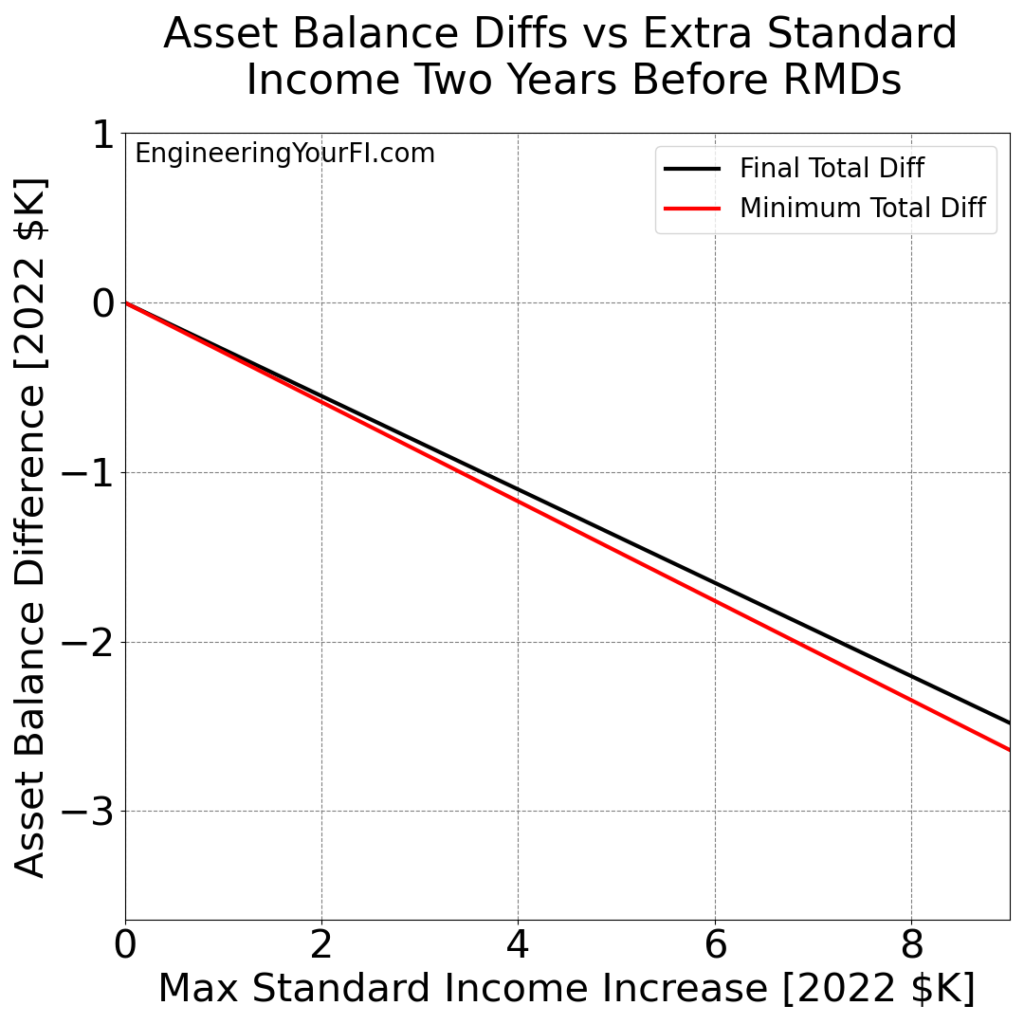

Two Years Before

Well maybe we just need to start earlier than one year before RMDs. Let’s try two years and see what happens.

Essentially the same result, except even lower differences.

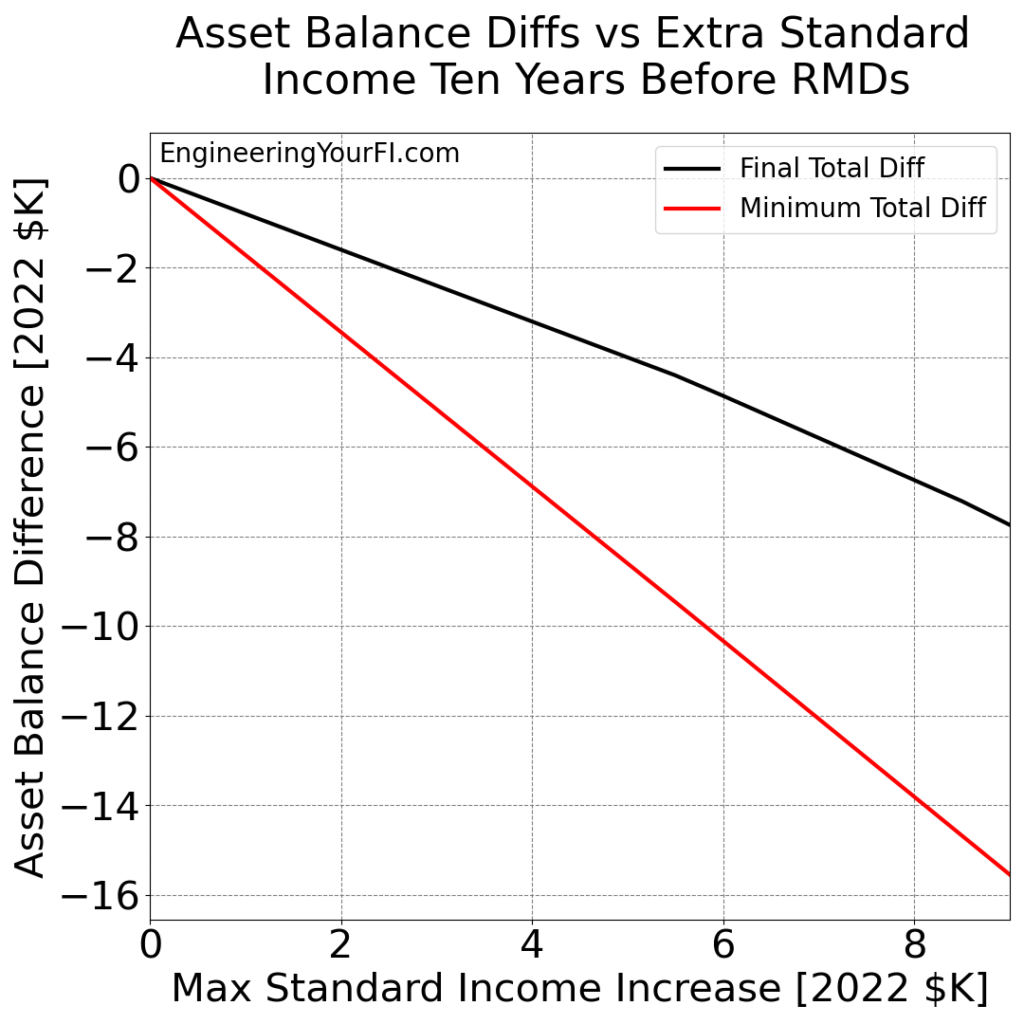

Ten Years Before

Let’s try 10 years beforehand, which is when a lot of folks realize they may be facing steep RMDs in their 70’s and beyond.

Again essentially the same linear trend downward, with even larger magnitude losses. However, there is a growing gap between Final Total Diff and Minimum Total Diff, and it looks like Final Total Diff is a bit less linear. So perhaps if we start even earlier, the Final Total Diff might finally rise above $0 at some point?

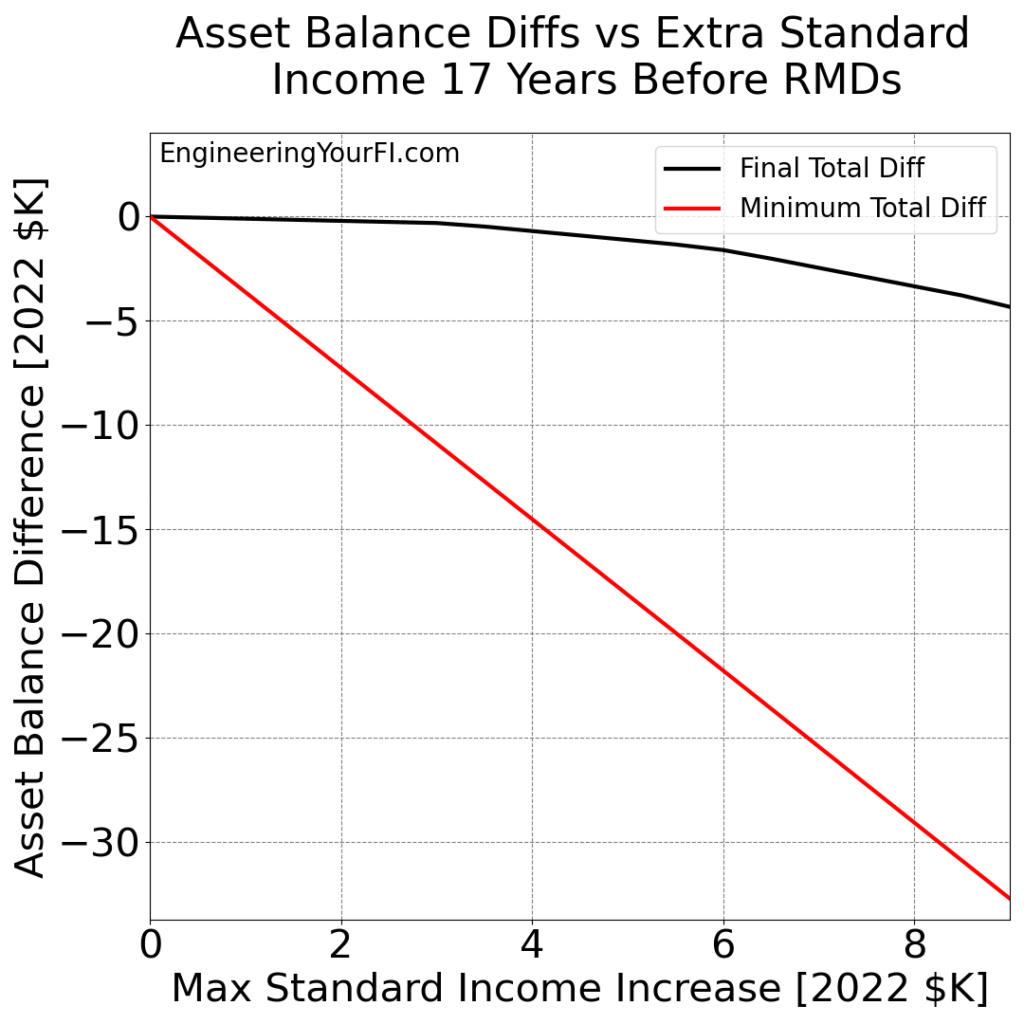

Halfway To RMDs (17 Years Before Age 72)

Next let’s try starting the additional withdrawals halfway from Chloe and Chris’ retirement start age (40 for Chloe, 38 for Chris) to the age RMDs will start (74 for Chloe, 72 for Chris): age 57 for Chloe, 55 for Chris.

Whoa, we’re now starting to see a pretty big difference in the Final Total Diff and Minimum Total Diff, with the Final Total Diff getting a lot closer to $0 (and gently curving away). But it still doesn’t surpass $0 at any point, and the Minimum Total Diff is getting quite large! Chloe and Chris could lose over $30K if they pull an extra $9K every year from their retirement accounts and they die earlier than expected.

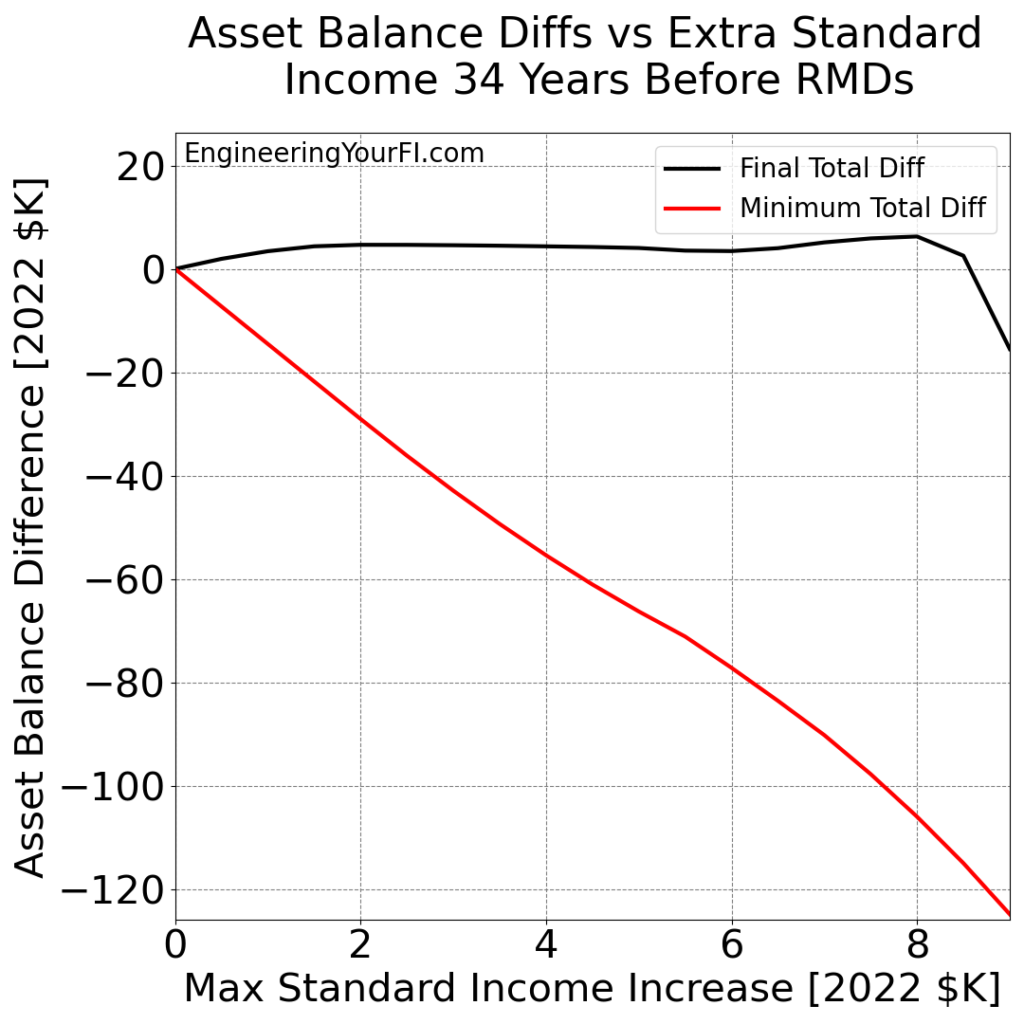

Beginning of Retirement

What if we start these extra withdrawals all the way back at the very beginning of Chloe and Chris’ retirement?

Alright, we finally have a Final Total Diff surpassing $0! Though the Minimum Total Diffs are dreadful – well over $100K with larger withdrawals.

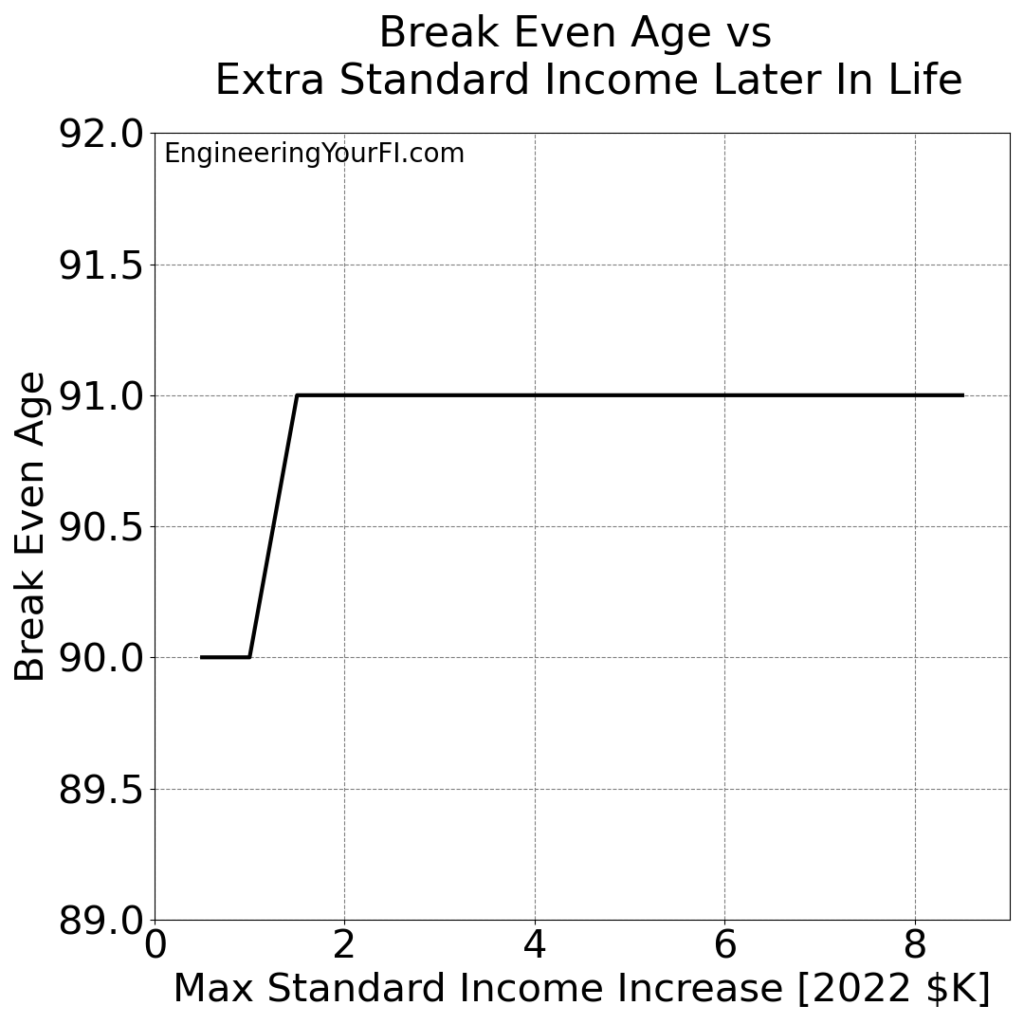

Now that we finally see some increases showing a net total benefit of withdrawing more from Chloe and Chris’s pre-tax accounts, let’s see when the “break-even” age (plotted for Chloe’s age) is for each withdrawal amount (i.e., how old Chloe is when the Final Total Diff surpassed the baseline case):

Wow, Chloe and Chris see absolutely no benefit from extra withdrawals their entire retirement until essentially the very end of their lives when Chloe is in her 90’s and Chris is nearly in his 90’s.

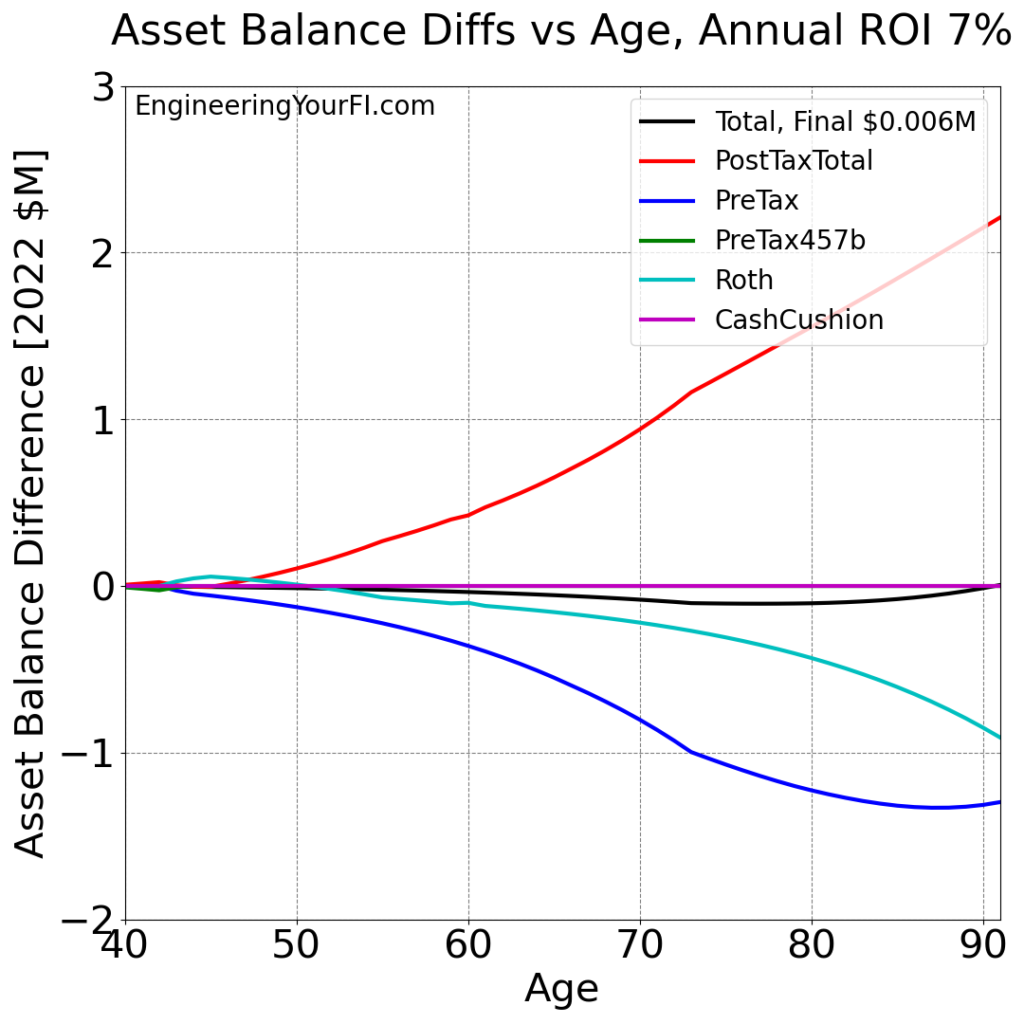

To better understand how they don’t break even until so late in their lives, let’s look at how the asset differences (vs the baseline scenario) evolve over time if they withdraw an extra $8K from their retirement accounts over their entire retirement (remember that you can employ a Roth conversion ladder to do this without penalty before age 59.5):

This plot shows how the Total Diff (black line) is below $0 for the entire simulation until the very end when it barely surpasses $0. Another unfortunate aspect of this approach: Chloe and Chris’ Roth IRA account is much lower at the end of their lives, which is not great for estate planning (since the Roth account is the best type of account to inherit – stay tuned for a future post about estate planning).

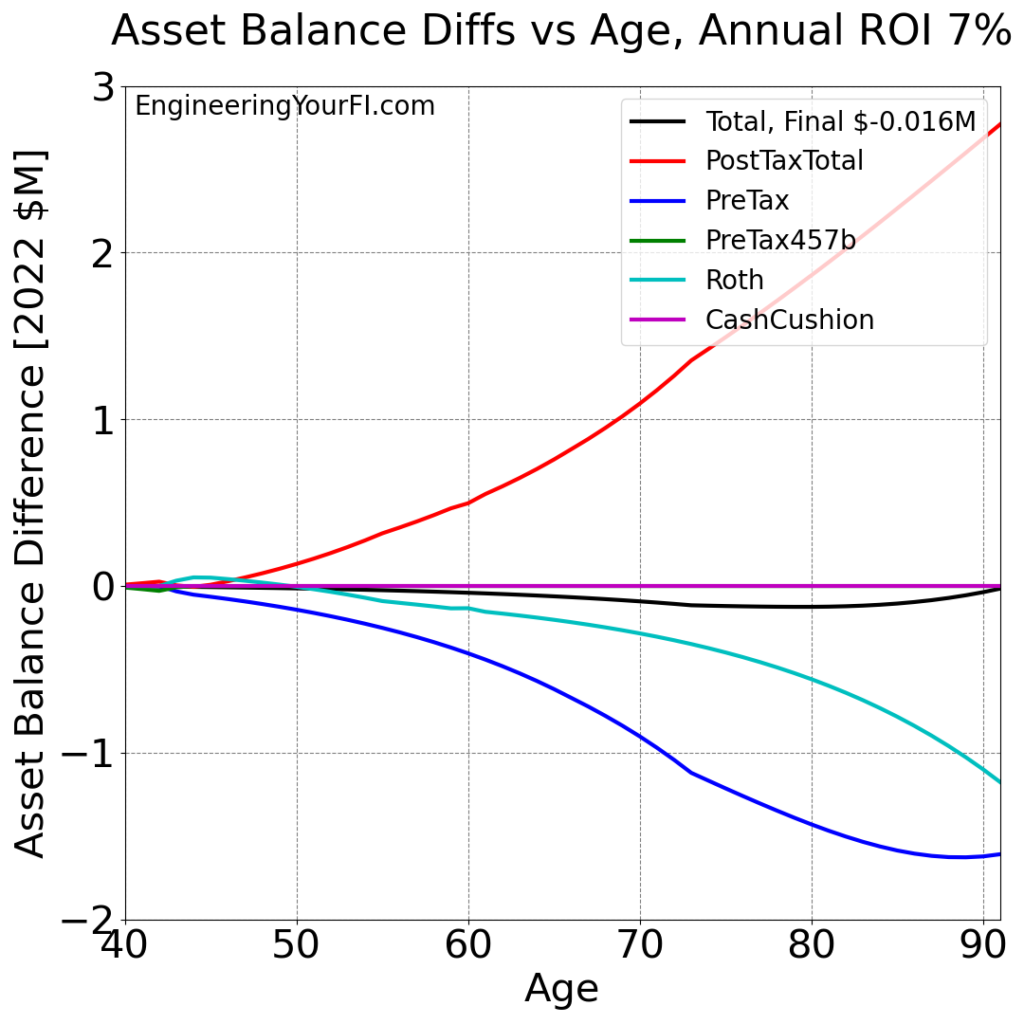

And unfortunately if Chloe and Chris withdraw a bit more than $8K, increasing to $9K, they will actually still lose money in the end:

So Is It Worth It? Don’t Think So

Both the back-of-the-envelope example and all the higher fidelity simulation results above indicate that taking out more than the standard deduction from your pre-tax accounts before RMDs start, in order to reduce your RMDs and thus taxes, is NOT a good idea.

In almost all scenarios, you’re only going to lose money. And even if you have decades to do this tax planning by retiring early in life, odds are you’ll only come out ahead in the very final years of your life.

And at the end of your life you’ll likely be sitting on top of the largest amount of money you’ve had your entire life, due to the magic of compounding returns. At that point it will be relatively painless to pay a bit more in taxes due to higher RMDs.

On the flip side, if you’re a brand new early retiree and facing significant sequence of returns risk, I don’t think it makes sense to pay MORE taxes at that point with the hopes that you’ll save a few thousand dollars in taxes in your 90’s.

And of course, you might die earlier than planned! In fact, the above scenario has Chloe and Chris only coming out ahead in their 90’s, but the average age of death in the US is 76.1. In which case they would have lost money overall in all scenarios.

An important note: I am drawing the above broad conclusion that it’s not worth withdrawing pre-tax funds early based on the above back-of-the-envelope example, the above higher fidelity simulations for Chloe and Chris, and my own intuition. However, there were many scenarios I did not consider, such as other filing statuses, different initial pre-tax balances, or a wide variety of other knobs that I could have turned. I’d be pretty surprised at this point if there was a scenario where taking more than the standard deduction before RMDs start is a really good idea, but I could be wrong! Please let me know if you believe such a scenario exists, and we can test it out.

Charitable Giving

Yet ANOTHER reason I don’t think it’s likely worth it to take more than the standard deduction before RMDs start: you can likely lower your taxable income after RMDs start by giving away much of the RMD to charity. In fact, you can deduct up to $100K of income that you donate to charity.

If you are like my wife and me, odds are you’ll be giving away a great deal of your assets to charity anyways, especially in your twilight years when it’s extremely obvious there’s no way you’ll run out of money.

Code

If you’d like to plug in your own values and play with different withdrawal scenarios to see if you can come out ahead with early withdrawals, you can download the code or modify and run the embedded Python interpreter below.

Modify the user inputs section at the top as desired, then hit the Run/Play (sideways triangle) button to generate the plots. To go back to the script to make any changes, hit the Pencil icon. If you want the text larger, hit the hamburger menu button, then scroll to the bottom to see larger font options. In that same menu you can also Full Screen the window, and other actions.

Conclusions

Overall, it’s a pretty clear cut answer in my mind: it is NOT worth taking more assets from your pre-tax retirement accounts than the standard deduction before RMDs start. The lost growth from the tax drag nearly always surpasses any tax savings by having lower RMDs (even if those RMDs result in much higher top tax bracket). And even in the case when you do save money in the end, it’s not until the VERY end of your life, when you likely have far more than you need, and paying more in taxes is far less dangerous to your portfolio than earlier in life.

But I’d still like to know if there is any scenario where you think it might be clearly worth it to do this (i.e., big tax savings and larger total net worth very soon after RMDs start). If so, leave a comment or shoot me a note.

Great graphics and analysis. RKO

Thanks!

Wow ! This is really amazing. I’ve been struggling with this issue for the last few years and keep delaying pulling more funds out of my deferred accounts. I’m going to play with your formula. My combined top marginal tax rate for state and federal would be about 29%. At age 63, that’s a lot of money to be paying in taxes for almost a decade. I’m already pulling about $2,000 out of an inherited variable annuity each month but I don’t need anymore. Lots to think about ! Thank you so much for this analysis.

Thanks Blake! Yeah I suspect at your age and top marginal tax bracket, it’s pretty unlikely it’ll be worth pulling from deferred accounts before RMDs kick in – the lost growth will likely more than offset any reduction in your RMDs. I will also admit though that I didn’t consider state taxes here – future post.